Quick reminder: I’m giving a free creativity workshop called Permission to Play on Saturday, May 11.

It’s easy for adults to forget that it’s okay to play—but that lack of play can keep us stuck! Join us for approximately 90 minutes and reconnect with your playful inner kid.

We’ll start at 1pm Eastern (New York) Time. Everyone is welcome, whether you have an existing creative practice or not. All you need is yourself, a pen or pencil, and some paper, though you’re welcome to bring materials for a quick drawing/doodle/etc. if you like.

We had a great time at the session yesterday, so I may add a third sometime soon, too—I’ll update you on that as I have details.

If you’d like to join us on Saturday—and I hope you will!—sign up here:

Please share this info with a friend!

Of all the things that happened in 1924, one you probably aren’t aware of is this: George Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue” premiered in New York City.

It was brand new. It hadn’t yet been licensed as an airline theme tune (which probably has had Gershwin spinning in his grave since the 80s). Nobody had ever heard anything quite like it. Every time I listen to it, I find myself wondering what it must have been like to hear for the first time in 1924, when it was not yet a classic, but something completely new.

The audience at Aeolian Hall went mad for it, but the critics were a mixed bag, often clearly having no idea what to do with it. Here’s one gem: Lawrence Gilman, whose favorite composer was Richard Wagner, wrote in a New-York Tribune review on February 13, 1924, “How trite and feeble and conventional the tunes are … how sentimental and vapid the harmonic treatment, under its disguise of fussy and futile counterpoint! … Weep over the lifelessness of the melody and harmony, so derivative, so stale, so inexpressive!”

“Lifelessness”? “Inexpressive?” Full disclosure: I’ve adored “Rhapsody” since the first time I heard it, and I have to wonder if Gilman heard the same piece. And the answer, I suspect, is no: His Wagnerian filters were trying to make sense of something wholly unlike Wagner, and therefore he was unable to really hear it. He was not Gershwin’s audience, and it shows, especially given the passage of time. (There’s absolutely nothing wrong with that, by the way—we’re all drawn to some things and repelled by others.) Of course, there were other critics who were much more enthusiastic, but I mention Gilman to bring home a point I’ve made before: don’t listen to feedback from people who are not your audience.

Fortunately for Gershwin, who was all of 26 years old and literally wrote the piece in a month, and his sponsor, Paul Whiteman, whose orchestra premiered it, the general public adored the piece. The word spread—and why not? If you’ve never been to New York City, the answer to this question may not be as obvious (though I’m sure you’ve seen enough movies and TV to have a decent feel for the place), but really, have you ever heard anything so evocative of New York? Especially 20th century New York?

I’ve just listened to it again, and there are so many moments I love, but my favorite just might be the moment when you can all but see the driver slam on his horn as all the pedestrians rush past.

As I listened, I was struck by the similarities between “Rhapsody” and Bernard Herrmann’s incredible score to North by Northwest, especially the opening theme—it’s by no means the same, and it’s far darker and more suspenseful, but you can definitely hear echoes—the busyness of the city streets, in particular. And, of course, that makes sense, since the film also opens in New York. I can’t confirm this suspicion, and Herrmann was fond of composers like Bartok and Stravinsky, so I could also be off base. Give it a listen and tell me what you think.

(You can also hear in this piece some foreshadowing of Herrmann’s more famous Hitchcock score, Psycho, which came out the following year.)

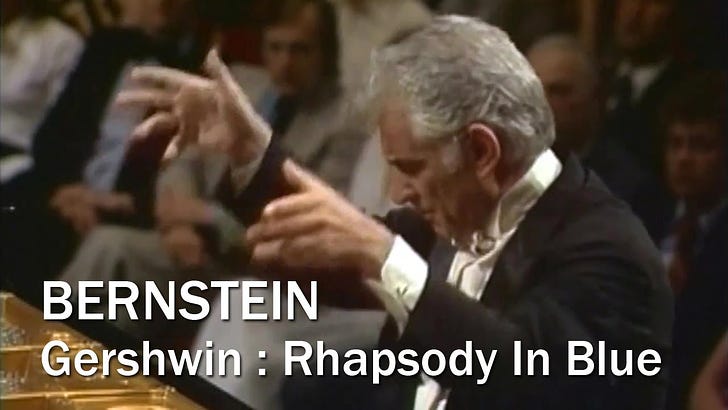

Back in my only somewhat misspent youth, I stole my mother’s CD of Bernstein playing and conducting “Rhapsody” with the Los Angeles Philharmonic. I couldn’t help it. I loved it too much. (Sorry, Mom! But I’m pretty sure I replaced it just as stealthily when I eventually found another copy…)

That recording also included the symphonic dances from “West Side Story” and Gershwin’s Three Preludes. As much as I love “Rhapsody,” I’m pretty sure I actually stole it for the second prelude, which is so specacularly sultry that my 20-something brain had to stop its usual whizzing when I heard it.

If you’re curious about the history of “Rhapsody,” the Saturday Evening Post has a great piece about it that gets into all the details much better than I could. It’s where I learned, at this late date, that Gershwin was Bernstein’s idol (which doesn’t surprise me one bit, honestly). It closes by noting that it’s best heard live with a great pianist. I’ve never had the chance to hear it live with an orchestra, but I did hear a combined senior recital in college where two of my choirmates performed a version for two pianos that was stunning, so even on that basis, I agree.

I know “Rhapsody” is on the long side (the other two are much shorter)—you’ll need about 17 minutes to listen to it—but if you haven’t already, or haven’t lately, I hope you will. My favorite way to listen these days is with a good pair of headphones, eyes closed, no distractions. (Remember when that was a thing, back in the day? My dad used to sit in a chair and just listen.)

In this particular case, I made an exception to watch Bernstein, and I recommend that, too. I don’t think I’d really appreciated the intricacy and athleticism required by that piano solo until I watched.

Either way, I encourage you to treat yourself to all three of these pieces, and I hope you can listen when you can devote some attention to them—great music deserves that, and so do you.

Who knows what inspiration might find you?