Five or six years ago, I interviewed a colleague for a staff profile at work, and she mentioned that her hobby was circus silks. She would go to classes every week to learn how to climb the two very tall strips of silk fabric like circus performers do.

It was certainly the most unconventional hobby I’d heard of, and I was surprised that it was even something taught in the area. She told me she learned through the Trenton Circus Squad. Wait, there’s a “circus squad”? What? And this has been going on in my back yard for how long?

I looked up the Trenton Circus Squad and went to their year-end performance. TCS was founded as an after-school program for kids in Trenton, both as a program in circus arts and to give them some help with homework. The show was pretty much what it said on the tin, featuring kids from the program juggling, doing balance routines, riding unicycles, walking on stilts, performing on the trapeze and silks, and more.

After the performance, I talked to the co-founder, Zoe Brookes, and said, “These kids are amazing.”

Instantly—and quite emphatically—she corrected me. “They are not amazing kids,” she said. “They are ordinary kids who do amazing things.”

It almost felt like being slapped in the face. What do you mean, they’re not amazing kids? I just watched them do things I couldn’t do without seriously hurting myself—and frankly wouldn’t have the courage to even think about trying. Why on earth would you not want me to think they’re amazing? But when I stepped back and thought about what she was actually saying, I realized it was a distinction worth considering.

Those kids were just normal kids from the Trenton, New Jersey, area—not an area with the best reputation. They’re fundamentally no different than you or me or anyone else we know. In fact, because we’re talking about the Trenton area, the sad truth is that a lot of them are less likely to be “amazing” than their more privileged peers.

The difference is that they’ve learned how to do something amazing, and they’ve learned to do it well.

Zoe’s comment not only pointed out that distinction, but said something else that’s equally important: If these kids can do it, any kid can do it. You can do it. We’re not gatekeeping “doing amazing things,” because “doing amazing things” is open to all.

When was the last time you decided that you couldn’t do something because you think that the people who do it are “amazing” (and were probably born that way) and you’re not? That you’re not good enough or special enough or, I dunno, up on that pedestal enough?

We think “ordinary” is an insult. We think it means we’re not good enough when it actually just means we’re normal.

I acknowledge that status, privilege, and literal mental and physical ability are factors that affect access to certain activities and resources. That said, human beings have an innate ability to learn, grow, and dream. The decisions we make about what we do with what we’ve been given, and what we haven’t, make all the difference—as the Circus Squad kids demonstrate.

We think “ordinary” is an insult. We think it means we’re not good enough when it actually just means we’re normal.

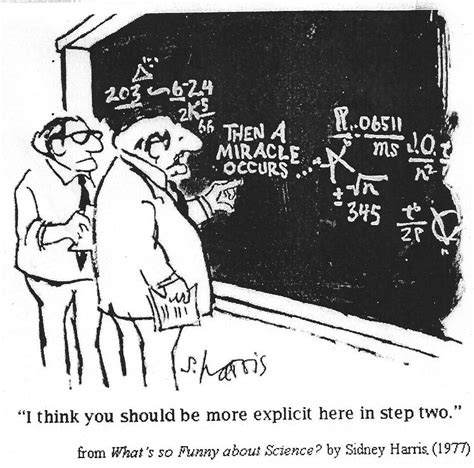

Back when I was teaching at a private school in the ’00s, I was astonished to discover that there were teachers who believed you couldn’t teach writing. They thought that you could teach kids to read, and you could teach them vocabulary, and maybe spelling and grammar (maybe!), and between that and teachers’ comments about what was wrong with their papers—assuming they understood those comments, of course—they would just…know how to write. Somehow.

I found the whole idea absurd. It’s like believing that if you teach kids the parts of a car and the rules of the road, they’ll miraculously understand how to drive.

Would you get on the road, or let your kid on the road, if we taught kids to drive that way?

I didn’t think so. Me, either.

None of us is born knowing how to do much of anything. We can’t speak, can’t walk, can’t feed or dress ourselves…we’re a bundle of involuntary processes, and that’s about it. We survive because someone cares for us until we’re old enough for them to teach us to do those things ourselves. And then we’re taught bigger things: to read, to do math, how science works.

I wasn’t born knowing how to write. I know how to write because I was taught to write, just like I know how to drive because I was taught to drive.

Those kids in Trenton have awesome circus skills because they were taught awesome circus skills.

Telling ourselves we have to be amazing in order to do something is gets it backwards. We’re all normal, ordinary people, but we can learn to do amazing things.

Sure, some of us have natural talents that mean we pick up some skills more quickly, or are more adept at them, but we still learn them, even if it doesn’t look that way to others (or even, sometimes, to ourselves). We did not arrive on the planet knowing how to do them, or even that they existed.

Every single one of us is ordinary, just like those kids in Trenton. We all start off ordinary, and we all end that way. It’s the things we do that are amazing or extraordinary, and we have control of those choices and those efforts.

We all start from where we are, too. Heck, I’ve spent the last five years recording podcast interviews from my walk-in closet, because that’s what I have. If I’d waited for a studio, I’d still be waiting. And I sure didn’t have any idea if I’d be any good at it at all.

(If you’d told me in 2018 that I’d end up having the chance to interview some of the people I’ve talked to from my lowly closet, I wouldn’t just have laughed at you—hard!—I would also have considered psychiatric help for you, which just goes to show that you never know where doing interviews from your closet might take you.)

Maybe the thing you think you want to do ends up not being the right thing for you. That’s okay. That just means it wasn’t your thing, and something else is. It’s not a failure on your part, or a character flaw. The only way you won’t find the right thing for you is if you decide you’re the problem and stop being curious about what else might be out there for you.

Let’s also be clear that “doing amazing things” doesn’t have to equal “doing flashy things.” It’s possible to do what you love without taking over the world. Oprah Winfrey rose from deep poverty to build a media empire, but your dream could be to perform regularly at local open mics, or to open a small shop to sell your handmade ceramics. “Amazing,” like so many things in life, is in the eye of the beholder, and for a lot of us, “flashy” can be overwhelming and not much fun. There’s no shame keeping things small if that’s what works for you.

The next time you start thinking you can’t do something because you don’t know how, and aren’t amazing or talented enough to learn how, I hope you’ll stop and remind yourself that “amazing” is about what you do, not who you have to be, and give it a try anyway.

Check out the Trenton Circus Squad kids below (and while I have no affiliation with them at all, if you find them as inspiring as I do, I’m sure they wouldn’t argue if you wanted to send a couple bucks their way to keep them going).

OMG, Nancy! I totally cried watching that video and seeing those kids shine. So sweet. I will definitely donate. They need this program in every town. Great and inspirational post as always.