As usual, you don’t have to be a fan to follow this post. You may want to become one as a result of reading it, though. ;)

This past Thursday marked the 60th anniversary of the longest-running science fiction show on television. It arrived in 1963 not with fanfare, but with a theme tune that immediately told viewers this was something different, thanks to the pioneering work of Delia Derbyshire and the BBC Radiophonic Workshop.

It’s the story of a show that could, and by all rights probably should, have been nothing particularly special, but has grown into a media juggernaut the likes of which, if I’m perfectly honest, I would not have believed was possible back when I discovered it in high school, relegated to whatever space your local PBS station could sacrifice for it, and largely unknown in the US.

But hey—the show’s always been bigger on the inside.

Back in November 2016, I started a list of things I’ve learned from watching this show as a lark. I figured it would be silly stuff like “Reverse the polarity of the neutron flow,” which makes exactly no scientific sense, not least because neutrons, by definition, have no polarity. Nonetheless, it’s a DW technobabble staple, and was one of the first things that came to mind when I started the list.

I quickly discovered that you run out of the silly stuff in a hurry, which meant I had to start digging a little more. I was surprised not only by what came to mind, but also by the realization that this goofy British show, which for so long had been held together with bubble gum and duct tape, had taught me a lot more than I realized. In fact, it had formed my worldview and my sense of morality far more than any school, church, or parent ever had. That’s more than a bit startling—and also a big reason why I love this show so much.

I don’t want to rehash that list here, and I could probably bang on about why I love this show for hours, so I’m going to try to keep it short. Well, short-ish. I’ve chosen three areas to focus on so we’re not here until next week.

Doctor Who is, fundamentally, a show about an alien—a Time Lord—who travels the universe righting wrongs. The Doctor fights for those who have no other advocate; he’s a champion of the underdog. The character is not a superhero, and doesn’t have any particular superpower aside from regeneration: the ability to change form and “cheat” death. If there was only one thing I could tell you about this show, and why I love it so much, it would be that the Doctor, as his former traveling companion Romana says in one of the audio stories (“Neverland”), “his unerring sense for what is right.”

Good vs. Evil

Themes of good and evil are obvious throughout the show—the serial that “made” Doctor Who was “The Daleks,” in 1963, in which the eponymous genocidal pepper pots were an obvious Nazi metaphor (their ringing and repeated cry of “EX-TER-MI-NATE!” just might have given it away). The story was the second to air and immediately cemented the show in the public consciousness, and set it up to explore “what is right” ever after. Here’s the Doctor’s first meeting with the Daleks, from the newly colorized version of the story:

To its credit, the show’s exploration of what is right extends to the Doctor as well as varied enemies. (“You can always judge a man by the quality of his enemies” is one of the things on my aforementioned list, and for good reason). Too many of our heroes are let off the hook, allowed to be The Good Guy—the proverbial white hat—without any introspection at all. Not this one.

There’s an entire story from the 70s that focuses on how the Doctor’s interference on one planet had unintended consequences, which of course, must be put right. It’s called “The Face of Evil,” and it’s one of my favorites for that very reason, among others.

Similarly, here’s an exchange from a 2010 audio story called “The Resurrection of Mars” (emphasis mine):

THE DOCTOR: I used to be that guy.

LUCIE MILLER: You mean, you're the Monk? It was you all along?

THE DOCTOR: No, but not far off—I was once a man with a master plan.

LUCIE MILLER: Oh.

THE DOCTOR: I’d seek out injustices, topple governments all in the name of the greater good. I’d started doing the maths, you see.

LUCIE MILLER: The maths?

THE DOCTOR: This is how evil starts—with the belief that the ends justify the means. But once you start down that road, there’s no turning back. What if you can save a million lives, but you have to let ten people die? Or a hundred? Or a hundred thousand? Where do you stop?

LUCIE MILLER: But you did. You did stop.

THE DOCTOR: I did. But by then I’d ended up travelling alone, because I couldn’t trust myself with anyone's life.

This is a character who is willing to look at internal flaws as well as external ones, which is more than most of us can say.

What’s “right” also includes saving others from pain the character has experienced firsthand. And it doesn’t leave out politics, either. War, famine, death, racism, corporate malfeasance, colonialism and indigenous peoples, the environment, authoritarianism (I swear everything I’ve ever learned about authoritarianism I saw on Doctor Who first). I can’t possibly say it better than this clip does.

As I said about this monologue elsewhere a few years ago:

It’s the most amazing argument against racism, violence, madness, us vs. them, division, the reality of war and destruction. It’s the most astonishing depiction of human nature and how easily we shatter ourselves and each other rather than doing the sane, rational thing and just listening to each other. Forgiving each other. Having compassion for each other rather than holding on to the deep human need to be right. Coming together rather than being driven apart.

It’s just as relevant now as it was in 2015, when it first aired. I wish I could send it to the Middle East right now, to be honest. And it’s from a show that is, at its core, a teatime show for kids and families.

Can you imagine anything like this coming from any other show written with kids in mind? If you’ve been wondering why it had such a big influence on me, now you know. I wasn’t a kid in 2015, but the show has always had moments like these. There’s an entire episode from the 70s called “The Mind of Evil” where the monster of the week kills by showing its victims the things they fear most and feeding off that fear. The Pull to Open podcast pointed to the way the story made clear the relationship between evil and fear:

Regeneration

As I mentioned above, the Doctor regenerates. In practical terms, that means the lead actor is swapped out for a new star every so often—a precedent brought on by the show’s success and the declining health of the actor who originated the role, William Hartnell. It’s a clever fix for an unfortunate problem, and one without which we probably wouldn’t be talking about this show today as anything other than an interesting footnote in TV history.

We’ve now had 15 actors in the role, with the 16th waiting in the wings (that’s counting John Hurt and Jo Martin, who each have appeared for an episode or two under special circumstances, if I have my sums right). When the show was relaunched in 2005, it was surprising to see someone like Christopher Eccleston, a well-known and highly regarded actor, in the role. The show then launched David Tennant and Matt Smith to superstardom before landing Peter Capaldi, who, like Eccleston, had a more established resume, and Jodie Whittaker—the first woman to take on the role. Ncuti Gatwa takes over later this year.

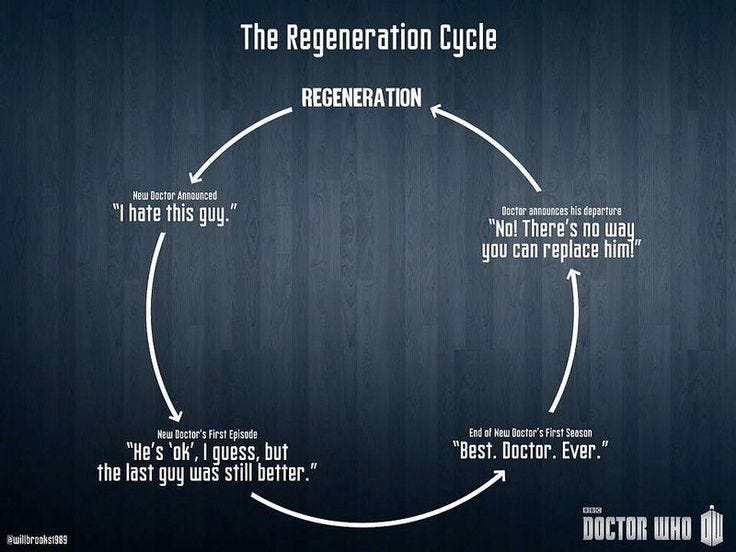

Fans’ reaction to this process is now so predictable that it’s been illustrated:

That’s pretty accurate.

The thing is, regeneration on this show goes way beyond the lead actor and general show lore. The whole show regenerates each time a new Doctor is cast, or when a new showrunner comes in. The vibe changes. The Doctor changes, in ways that can be dramatic or more subtle. The writing, priorities, and tone of things is different. Traveling companions come and go.

The entire show is a revolving door, and that’s a great thing, because it basically guarantees there’s something for everyone. Don’t like this companion? Wait a bit; there’ll be a new one. Not wild about this Doctor? Again… wait five minutes and the weather will change. The TARDIS—the Doctor’s time machine—will change, too.

Change is literally the lingua franca of this show. If you’re not fond of change, this is not the show for you. Some fans of recently found this out in a very direct way with the decision to render a previously disabled villain able-bodied in an effort to correct the “evil disabled villain” trope.

This decision has caused an immense amount of controversy, and the debate rages on. It raged on in my head for several days, to be honest—while addressing the issue is the right decision, no question, was this the best way to do it?

I’m not sure it was, but I am sure of this: there is no Doctor Who without change. The main character regenerates regularly, and so does the show itself. To declare that it has to remain a stodgy product of the 60s is to condemn it to death. Change is at the core of how it’s survived for so long.

With a fandom now in the millions, as a mainstream rather than cult series, the show also has the chance to spark conversation in a way most shows don’t (or won’t)—and in a way most of us can’t do on an individual basis. There’s a long overdue conversation about disability, representation, and stereotypes happening in this fandom now that is large enough that it could have repercussions outside the fandom. I can’t imagine any role more fitting for Doctor Who.

Fandom

My original Doctor Who fandom was breathtakingly small: there were three of us. One lived halfway across the country, and the other two of us went to the same school. It was a bit isolated, but I’ll admit I sometimes miss it. It is possible to have too much of a good thing.

That said, watching this fandom grow (dare I say “explode”?) over the last 20 years has been something to behold. Being a Doctor Who fan used to carry the connotation that you were a weirdo with nothing better to do on a Saturday night than watch a show with wobbly sets and monsters made of green bubble wrap.

It’s hard to explain the feeling when I visited London in March of 2005, just days before the new series premiered. Walking into London Bridge station and seeing this massive poster high on the wall was both exciting and surreal.

(Watching the promos on the BBC, knowing I’d be back home a day or two before the premier, on the other hand, was just torture.)

Fandom has only grown since then, but it would be remiss of me to imply that it was tiny at that time, especially in the UK. It’s bigger now, but it was a force to be reckoned with back in 2005, too.

In fact, one of the things I most love about the Doctor Who fandom is its ingenuity. I think we’ve taken the best quality of the Doctor and made it our own. There will be an actual police box on display at a con because someone decided to build one and bring it. Someone will turn up in a cosplay that is so intricate it takes your breath away. Vendors make cool things based on characters or ideas from the show. The whole thing is a celebration not just of a TV show, but of the creativity it brings out in its fans.

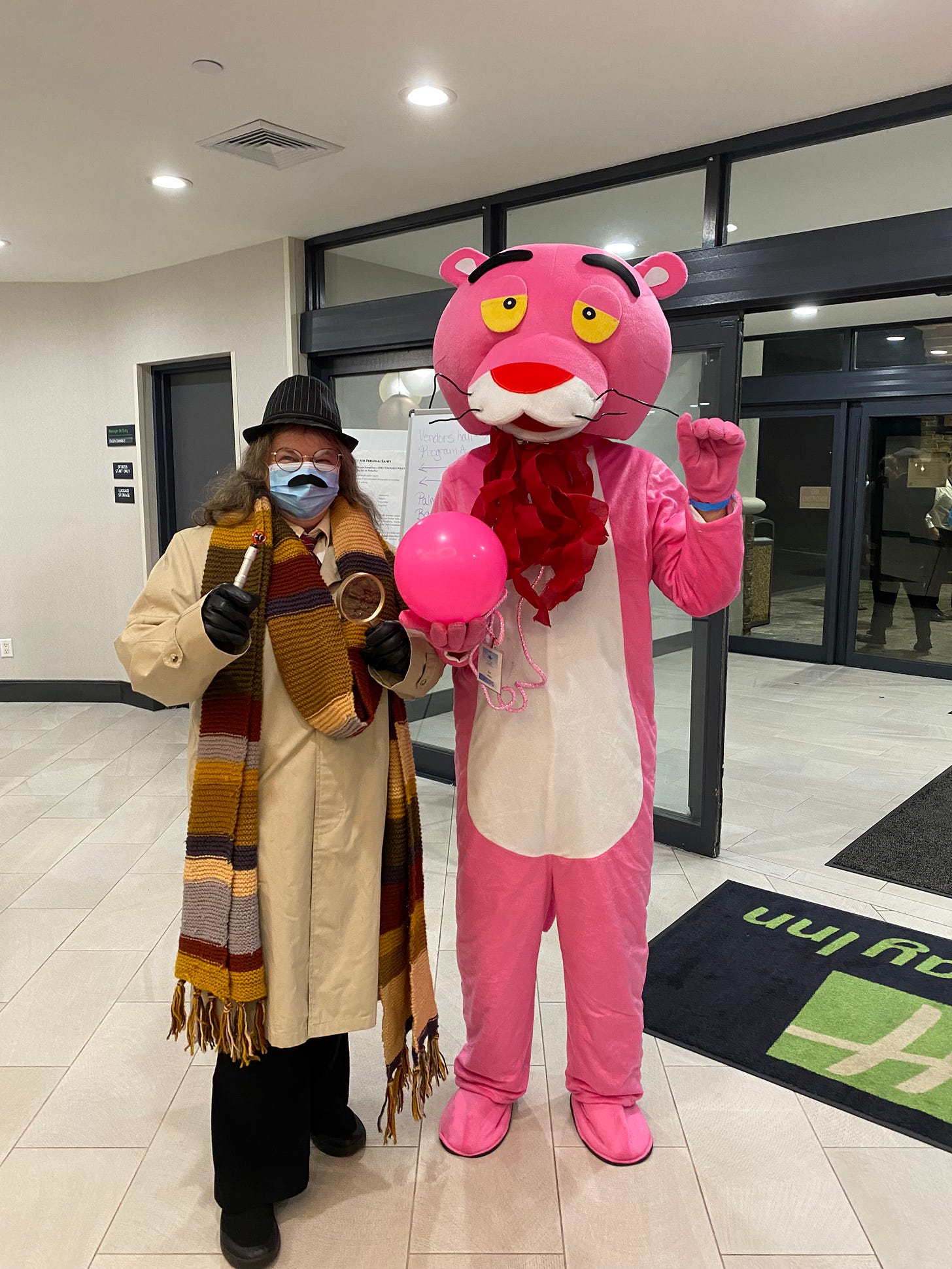

For instance, here’s a brilliant DW/Pink Panther mashup from two years ago, crossing the Fourth Doctor with Inspector Clouseau and an Ood with the Pink Panther:

And it was DW that really got me writing as a kid, because I often wasn’t allowed to watch TV, so I decided I’d go write my own stories instead. Back then I had no idea what fanfiction was, though I did end up writing some later, before I decided it was time to write my own original stories instead. I’m far from the only fan to have started writing because of a TV show, especially this one.

Taking it a step further, fans have grown up to write for the show itself, to run the show, and to star in it. David Tennant and Peter Capaldi were dedicated fanboys long before they ever got a chance to set foot in the TARDIS. Peter Davison tells a story in his book about David Tennant running into him years before the new series launched, fanboying and seeming to know more about Peter’s time on the show than Peter himself did—and Peter himself is a fan, as he mentions on the podcast. David talked about his fanboy past here:

And Graham Norton made Peter Capaldi own up to his teenage fan letters here:

On top of that, all three modern showrunners—Russell T. Davies, Steven Moffat, and Chris Chibnall—were super-geeky fans as kids.

As if that’s not enough, an entire company, Big Finish, sprang out of the minds of Gary Russell and Jason Haigh-Ellery, who managed to secure a license from the BBC to produce original, full-cast Doctor Who audio stories—starring the original actors—in the early 2000s. Gary told me that whole story for the podcast, which you’ll get to hear in January, and it’s one I love because it proves that fandom can lead to wonderful things, including a company that has branched into wider territory over the years, including original dramas and adaptations of classics like Sherlock Holmes and The Prisoner.

It’s not all about being a hopeless anorak or being into cosplay.

All right—if you made it this far, thanks for sticking with me. I maintain this post is still “short-ish,” in the sense that it could have been a whole lot longer, because there’s so much to love about a show that’s survived for six decades and isn’t stopping.

If you’ve never watched Doctor Who, I simultaneously feel sad for you and jealous of all the wonder that awaits you if you decide to jump in. It’s a BIG Whoniverse, with a lot to discover, not only on TV, but in novels, comics, games, and the Big Finish audioverse.

If you take nothing else away from this post, I hope it’ll be an appreciation for the Doctor’s raison d’être, which the show articulates so well here:

I’ve never watched it!! But you have convinced me to give it a whirl. Do you recommend starting with the very first one? Or is it okay to start later?